The Changing World of Mongolia's Boreal Forests

by Kate Evans

with additional reporting by Leona Liu and Bulgamaa Batjargal

Photographs by Cory Wright, Gantulga Tumurtulga, and Nasankhuu Otgonbulga

Every year as the sun warms and the days lengthen, 28-year-old Baganatsooj moves his herds to their summer pastures outside the town of Tunkhel in Mongolia’s far northern Selenge province – a nomadic lifestyle his ancestors have practiced for thousands of years.

The snow has melted, and Baganatsooj’s 300 sheep and goats, 40 cows, and 30 horses graze in the wide green valley. He heard through word of mouth that the rains have been good here, so, along with his wife Munkherdene and two children, travelled 50 kilometres with their livestock to their new home.

But it’s not just the weather that determines where the herder and his family set up their ger, or traditional yurt.

They also follow the forest. “Forests generate more water, and the grass is good there, so the animals graze at the edge of the forest,” Baganatsooj says. The trees also provide scraps of fuelwood and timber for temporary fences.

Life is changing for traditional herders – who make up a third of Mongolia’s total population – and for everyone else, too. In 1990 the country transitioned from socialism to a market economy, the new freedoms leading to a quadrupling in the number of livestock. Urbanisation is also increasing – the population of the capital Ulaanbaatar has grown by 70 percent since the 1990s.

More importantly for the herders, the weather is becoming less predictable.

Baganatsooj has noticed changes even within his working life: “Ten years ago the grass was very good. Now it’s getting drier. Last year was the driest year in a long time and there was lots of fire.”

In Mongolia, the effects of climate change are already being felt.

Average annual temperatures in Mongolia warmed 2.1 degrees Celsius between 1940 and 2014 – around triple the global increase over the same period – and Mongolian tree-ring records indicate that the 20th century was one of the warmest centuries of the last 1200 years.

Herd animals have been devastated by repeated dzuds, a local term for a peculiarly Mongolian natural disaster – a dry summer followed by a harsh winter. Drought affects grass growth, and less grass means livestock are unable to put on enough weight to survive the winter cold.

The phenomenon used to occur around once a decade, but there have been at least seven dzuds since 1998. In the worst, in 2009-2010, nearly 10 million animals died.

Nearly ten million livestock died during the 2009-2010 dzud. Credit: UNDP Mongolia

Nearly ten million livestock died during the 2009-2010 dzud. Credit: UNDP Mongolia

Climatic changes are driving further migration, says Oyunsanaa Byambasuren, the General Director of the Department of Forest Policy and Coordination at the Mongolian Ministry of Environment and Tourism (MET).

Oyunsanaa and colleagues used tree-ring data to analyse the frequency of droughts over the past two millennia, and found that the recent dry spell is abnormal.

“We haven’t seen anything like it in the last 2000 years – we did not have such a frequency of droughts. It is making people lose their livestock or their livelihoods, and they’re moving to the city or more central places in order to seek a better life – and once they move, they don’t go back.”

“It’s scary, really. The seasons are very different, the forests and pastures are under pressure,” he says.

“People who are 40 or 50 years old say, ‘when I was a child, the situation was very different.’ Now, it’s completely unpredictable. Climate change is happening right now.”

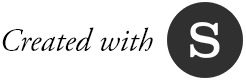

Mongolia is known for its steppes and deserts, but it is a forest nation, too.

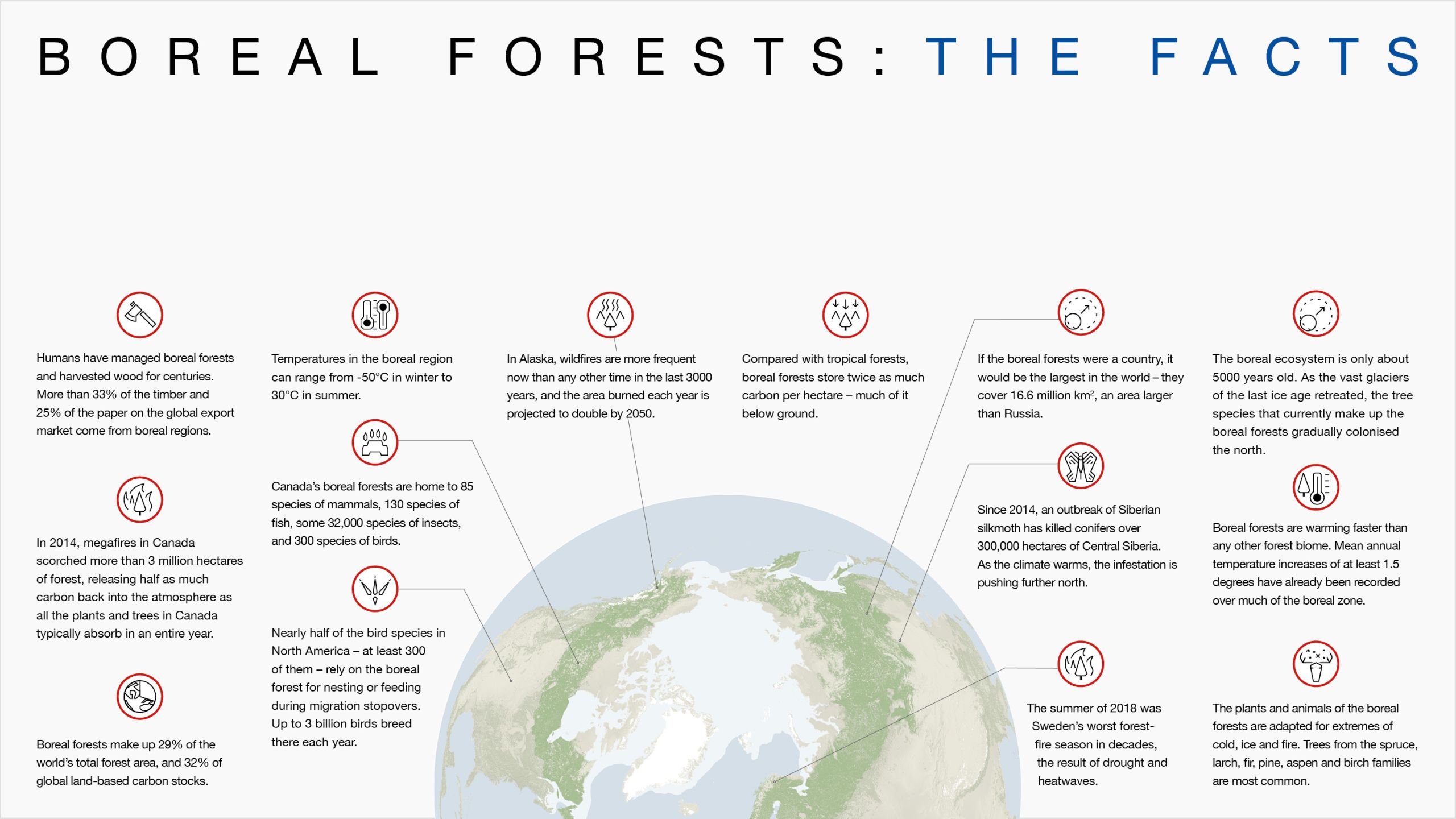

Boreal forests – dominated by larch, pine, and birch trees – line Mongolia’s northern border with Siberia, covering 14.2 million hectares, or nine percent of this vast country.

They are part of a huge expanse of boreal forest – the world’s largest terrestrial biome – that stretches right across the earth’s northern latitudes. These forests are both intensely affected by climate change – recent studies have found that the hotter, drier summers inhibit tree growth in Mongolia’s forests – but they are also a possible, partial solution to it.

Mongolia’s boreal forests provide important benefits for the country.

Wolves, bears, lynx, elk, deer and boars thrive here. Hawks, falcons and owls hunt from the skies, while pelicans, hooded cranes and numerous other birds spend part of the year in the nearby lakes.

The forests store large amounts of carbon and methane in both the plants and soils, and can help to increase water availability. They also prevent erosion on steep mountainsides, and are a natural barrier against the encroaching desert, says Noosgoi Enkhtaivan, Senior Officer for the Department of Forest Policy and Coordination at Mongolia’s Ministry of Environment and Tourism.

“Our forests act like green walls preventing desertification,” he says.

They are also a source of fuelwood, timber, nuts, berries and honey, and contribute to the livelihoods of rural people in diverse ways.

Bold Otgonbayar is 19 years old, and lives in the mountains of Mongolia’s far north, near Lake Khuvsgul. It’s a beautiful place, he says proudly, pointing out the high rocky bluffs, forested slopes, lush pastures, and remote lakes.

Like many others in the area, Otgonbayar and his family gather fruit in the forest to supplement their income. Between seven adults and a few children, they can harvest significant amounts of redberries, blueberries and gooseberries.

“In an average summer we would pick around two tonnes of fruit,” he says.

Families like Otgonbayar’s sell the fruit to local jam companies, and use the extra money to support their livelihoods and send their children to study in Ulaanbaatar. Teacher Baldanosor Tsetsegmaa says family members pass on knowledge about the best areas to harvest.

“One woman set a new record picking 96 kilograms of berries in one day!”

Jam-making is a relatively new business. A decade ago, a politician from the area opened a jam factory in the town of Murun, the capital of Khuvsgul province. Now, the town boasts at least ten jam and juice plants, each bottling up to 25 tonnes of fruit a year.

During the socialist era, access to Mongolia’s forests was strictly controlled. But the economic opening of the early 1990s was accompanied by environmental damage, says Dainagul, the manager of a small wood business in the timber town of Tunkhel, in Selenge province.

“There were years of uncontrolled use of forest resources because everyone was cutting down trees,” she says. “Things finally got better after the government restricted logging to enterprises like ours with a valid permit.”

Every spring and autumn, as part of a government plan to increase community participation in forest management, Dainagul’s 50 employees collect fallen wood in the surrounding forests. Removing the dry wood reduces the fire risk, and Dainagul uses it to make charcoal, a lower-emissions alternative to the coal normally used for heating.

Getting permission to use forest resources is much easier for companies like Dainagul’s than it is for individuals. Households must band together and collectively apply as a Forest User Group (FUG) at the district level – and then face a lengthy bureaucratic process before approval is granted.

Since the scheme began in 1995, 1281 FUGs have been created, and are now responsible for managing almost a fifth of Mongolia’s total forest area.

But unlike private companies, FUGs generally don’t have permission to harvest timber – they can only collect deadwood and non-timber forest products like berries and nuts. This is the cause of some frustration.

“We work as protectors and cleaners of the forest,” says Batbaatar, a member of the ‘Tusgal’ FUG in Tunkhel. “But there is very little to be earned from it, so it’s more like charity.”

Some FUGs have found a way to make a profit despite the restrictions.

49-year-old Buyan-Orshikh heads the ‘DX-Oyu’ FUG in Tunkhel, a group of 12 master carpenters and yurt-builders. He applied for a special permit, enabling the group to thin trees as well as collect deadwood. They select the best wood for their yurts, then divide up the rest for fuelwood.

Previously, Buyan-Orshikh had to buy expensive timber from the market, as deadwood wasn’t strong enough for a sturdy yurt frame. Now, with permission to thin standing trees, he no longer has to buy any, and has doubled his income. For his family of three children, including one with Down Syndrome, that’s made a big difference.

“People in this community are dependent on forests for our livelihoods,” says Buyan-Orshikh. “We need better options to take care of our families.”

Grazing also contributes to forest degradation in Mongolia.

During the socialist era, the number of livestock in the country was constrained to around 20 million. Once the restrictions ended, that swelled to 33 million by 1999 and 84 million by 2018.

And as repeated dzuds and droughts have taken a toll on more marginal grazing areas, many herders and their animals have moved from the steppes to the more central, forested part of the country, says Oyunsanaa. Boreal forests grow particularly slowly, and all those hungry mouths take a toll on the forest’s ability to regenerate.

“Animals like grazing in and around forests because the grass is greener and it is often close to a water source,” says Enkhtaivan, from the Ministry of Environment and Tourism.

That’s part of the reason Baganatsooj keeps his herds close to the forest. But he’s a member of an FUG himself, and says his herder father taught him about natural regeneration.

“I know that my animals should not eat young plants,” he says. “I don’t let my animals into the forest, just around the edges.”

Not everyone is as careful, Enkhtaivan says. “A lot of herders are not aware of the negative impacts that grazing can have on our forests.”

“So our Ministry is working with the Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Light Industry to give recommendations on pasture management laws and encourage the building of fences around forest areas.”

Fences won’t keep out the two other major threats to Mongolia’s forests, though.

Fires and insect pests have always been a natural part of the boreal ecosystem, but climate change and human activity are upsetting the balance.

Globally, forest fires are causing increasing devastation.

The summer of 2018 was the worst fire season in decades for Sweden’s boreal forests. In North America, the number of lightning-caused forest fires has risen between 2 and 5 percent a year for the last four decades.

Across the boreal region, fires are anticipated to increase dramatically as the climate warms, with far-reaching consequences for the environment and people.

Credit: Fire Management Resource Center-Central Asia Region (FMRC-CAR)

Credit: Fire Management Resource Center-Central Asia Region (FMRC-CAR)

In 2017, there were 206 forest and steppe fires in Mongolia. The majority occurred on the steppes, but more than 80,000 hectares of forest burned. Fires lead to forest degradation, and can even transform forests into steppe.

But it's not yet clear whether the dramatic climate change experienced by Mongolia is making the forest fires worse.

In another tree-ring study, the University of Mongolia’s Oyunsanaa and colleagues examined the frequency of fires in Mongolia’s north-eastern Khentii mountains over the past 450 years.

The researchers found that greater fire activity is associated with periods of drought – but surprisingly, even as temperatures warmed dramatically, fires did not actually increase in frequency over the last century. That could be because intensive grazing reduced grassland fuels and limited widespread fire, Oyunsanaa says.

Credit: Fire Management Resource Center-Central Asia Region (FMRC-CAR)

Credit: Fire Management Resource Center-Central Asia Region (FMRC-CAR)

Insects that eat leaves and needles are, however, causing increasing damage in Mongolian forests. The Siberian silk moth and the gypsy moth are the most destructive. Their caterpillars eat young leaves, weakening and killing even healthy trees.

As in other parts of the boreal region, the magnitude and severity of pest epidemics has increased, says Oyunsanaa, and outbreaks are happening at latitudes and altitudes that weren’t previously affected.

“In some areas the trees are totally gone – there’s no recovery, the trees are all dead. The infestation area is getting larger and larger.”

Siberian silk moth larva feeds on Siberian larch tree. Credit: John H. Ghent, USDA Forest Service

Siberian silk moth larva feeds on Siberian larch tree. Credit: John H. Ghent, USDA Forest Service

The impacts of climate change, fire and pests are cumulative, says Werner Kurz, an ecologist at Canada’s Pacific Forestry Centre in British Columbia. He’s an expert in the major boreal forest pest there – mountain pine beetles – as well as a contributing researcher to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

Warmer winter temperatures can enable pests to expand their range, Kurz says, while drought and water stress make trees more susceptible to insects. Where pest infestations kill large numbers of trees, fires burn more easily and intensely – and release more carbon.

Kurz has seen the results for himself in the Canadian boreal forests. “After the fire passes through, there’s no more organic matter on the forest floor. Many of the standing trees are blown down by the wind-storm generated by the fire, and the material on the ground is just a white line of ash.”

“That has huge implications for carbon release, and for the water-holding capacity of the forest floor.”

As temperatures climb, Mongolia’s permafrost is shrinking, too. Permafrost is ground, rock or soil that remains frozen for more than two years in a row. In Mongolia, it’s found across the country’s north, over much the same area as the forests.

That’s no coincidence – in arid regions, permafrost can increase the amount of moisture available in the ecosystem, says Yamkhin Jambaljav from the Institute of Geography-Geoecology at the Mongolian Academy of Sciences.

“The complicated interaction between the forest and the permafrost maintains stable conditions in the ecosystem,” he says.

To measure the extent of Mongolia’s permafrost, Jambaljav and his team covered 24,000 kilometres over several years, as they criss-crossed the country. They drilled 120 holes of up to 15 metres into the frozen ground to measure the temperatures beneath.

They found that five percent of Mongolia’s permafrost – 13,150 square kilometres – had thawed completely between 1971 and 2015.

In 1971, temperatures were low enough to support some form of permafrost in 63 percent of the country. By 2015, that had fallen to just 29.3 percent.

In the Khangai mountain range, the southern boundary of the permafrost had migrated north by 94 kilometres, and shifted up 900 metres in altitude.

The thaw is caused by climate change – but also amplifies it.

Plants and animals have been living and dying in the boreal region for thousands of years. Where the ground is frozen, it prevents their remains from decaying, storing the carbon in the soil and keeping it out of the atmosphere.

But if the soil thaws, microbes decompose the ancient carbon and release methane and carbon dioxide.

It’s estimated that the Northern Hemisphere’s frozen soils and peatlands hold about 1,700 billion tonnes of carbon – four times more than humans have emitted since the industrial revolution, and twice as much as is currently in the atmosphere.

In 2011, scientists from the Permafrost Carbon Network estimated that if they thaw, that would release around the same quantity of carbon as global deforestation does –but because permafrost emissions also include significant amounts of methane, the overall effect on the climate could be 2.5 times larger.

What impact will climate change have on boreal forests?

Will the warming feed the warming?

The answer to that question? It depends, says Werner Kurz. (Policymakers get frustrated with that answer, he says, but it’s true.) “From a scientific perspective there is huge uncertainty about what the role of the boreal forests will be in future climate change.”

In some parts of the boreal, warming temperatures, fewer frost-free days, and longer growing seasons could actually make forests grow better. That would allow them to absorb more carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and become better carbon sinks.

In other areas, thawing permafrost, increased fires, pest outbreaks, and land-use change could all exacerbate the release of greenhouse gases.

On balance, whether the increased growth will outweigh the negative effects – or vice versa – is incredibly hard to predict, says Kurz.

“We have a whole bunch of processes that will be changing as a result of climate change. Many of these will enhance growth, and many will accelerate decomposition – and frankly there is not a scientist in the world right now that could claim with a straight face that they could predict the outcome of these changes.”

Crucially, the risks are asymmetrical. It can take a century for a forest to grow – and a matter of hours for it all to go up in smoke.

“For boreal forest stands to reach maturity and maximum carbon storage, many decades of survivable growing conditions must prevail,” Kurz says. “But it only takes a single extreme event such as drought, fire, or insects to kill trees or whole forest stands.”

So what can be done?

Two things have to happen at the same time, says Kurz, if we’re to avoid runaway climate change, and meet the goals of the 2015 UN Paris Agreement to keep global temperature rise to less than two degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels.

“We cannot do that without simultaneously massive reductions in fossil fuel consumption, and managing the land in such a way to contribute the greatest possible sink – so that it keeps sucking carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere but also provides a continuous supply of timber, fibre and energy to meet society’s demands.”

That means preventing forests from becoming farmland or desert, fighting the fires and insects, and encouraging local people’s involvement in protecting their forests.

Mongolia has taken up the challenge.

Alongside other efforts by the national government, the country is also the first outside the tropics to begin preparing for REDD+, an international climate change mitigation scheme under the UNFCCC that aims to assist developing countries to protect their forests and the carbon stores within them.

Khishigjargal Batjantsan grew up a city boy in Ulaanbaatar, but spent his childhood summers in the countryside with his herder grandparents, where he gathered blueberries and learnt what the forests meant for herders.

Now, he’s the National Programme Manager of the UN-REDD National Programme in Mongolia, which has been assisting the country to develop the capacity needed to meet the requirements of REDD+.

“We have a long-standing relationship with our natural ecosystems, including forests, because of our nomadic traditions,” he says.

Mongolians established the first national park in history, he points out – the sacred mountain Bogd Khan Uul was declared a protected area in 1778, and there’s some evidence its protection dates back even further, to the time of Genghis Khan in the 13th century – and despite the rapid pace of change in the country, forests are still a key part of Mongolians’ identity, Khishigjargal says.

The UN-REDD Programme will soon come to an end, but the country’s REDD+ strategy will continue, he says. “In our vision we aim to make Mongolia’s forests more resilient to climate change, while supporting livelihoods and the wood industry."

That includes finding smarter ways to tackle fire and pest outbreaks, reducing the area affected by forest fires by 30 percent – and could also involve easing the restrictions on community groups’ use of the forest.

Khishigjargal believes that allowing local people to harvest some timber will lead to better environmental outcomes. Since the FUGs were established in the mid-1990s, he says, there has been a reduction in both fires and illegal logging.

“But at the same time there’s not much motivation for FUGs to protect their forests if they don’t have the right to use it for certain purposes. At the moment it’s all responsibility, and few rights.”

The idea is still controversial, and Khishigjargal emphasises it would need to be tightly regulated. “Opening up the forest has to be very carefully done, because once you do, if it’s not well utilised it could lead to more deforestation.”

What’s important, says Oyunsanaa – who is also the National Programme Director of the UN-REDD Programme – is that scientists and policymakers, local people and NGOs, all work together towards a common goal.

“This is a challenging time for us. We are a society in transition, and at the same time the environment is rapidly changing, too.

Climate change is clear, and it is already influencing our people and our forests. We need more detailed research into these connections, and we need to take action, together.”

Oyunsanaa Byambasuren

In the valley outside Tunkhel, Baganatsooj the herder isn’t sure what the future holds. He would like his young son to follow in his footsteps. He wants to teach him the ways of the herder, just as his father taught him.

But his wife, Munkherdene, wants to take the children to the city when they’re older, so they can get an education. It’s a tough choice faced by traditional families all over Mongolia.

The old ways are becoming harder as the climate gets harsher. Whatever they choose, Munkherdene is clear.

“Forests are essential for our life,” she says. “We should regenerate them and preserve them for our children – and the next generation after that.”

If you enjoyed this story, please share with your networks using the buttons above.

For more information, visit:

Follow us on Facebook:

https://www.facebook.com/Reddplusmongolia/

https://www.facebook.com/UNREDDprogramme/

Talk to us on Twitter:

https://twitter.com/ReddPlus_MGL

This story was prepared in 2018 by the UN-REDD Programme and the Mongolia National UN-REDD Programme. It was made possible through the generous support of the European Union and the governments of Denmark, Japan, Luxembourg, Norway, Spain and Switzerland.